Plastic contamination in fulmars in the European Arctic over 25 years

By: France Collard, Felix Tulatz, Eirin Husabø, Stine C Benjaminsen, Rupert Krapp, Hallvard Strøm and Geir W Gabrielsen // Norwegian Polar Institute, Dorte Herzke and Mikael Harju // NILU – Norwegian Institute for Air Research, Claudia Halsband and Kjetil Sagerup // Akvaplan-niva, Arnaud Tarroux // Norwegian Institute of Nature Research, Jóhannis Danielsen // Faroe Marine Research Institute, Kate Anderssen // Nofima

The northern fulmar Fulmarus glacialis – hereafter called fulmar – has been used for biomonitoring of plastic pollution in the North Sea region since 2002. It has higher loads of ingested plastic than other seabirds, because it feeds exclusively at the sea surface where light-weight plastics float. Hard particles, such as plastics, accumulate in the gizzard, one of their stomachs.

Fulmars have two stomach compartments, first the proventriculus and second, the gizzard, separated by a narrow constriction that prevents the bird from regurgitating the gizzard’s content. Therefore,when hard particles are too large to pass through to the intestine, they accumulate in the gizzard. There, they undergo a grinding process, until they are small enough to reach the intestine to eventually be egested.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the North Sea, fulmars are well studied through monitoring programmes which mostly use adult fulmars that have been beached or caught accidentally during fishing activities. In the Arctic, in contrast, data are lacking, especially in the European Arctic (in contrast to the better studied Canadian Arctic). To make the fulmar a good bioindicator of plastic pollution also in the Atlantic sector, better data coverage is required.

Through the PlastFul project, funded 2019-2021 by the Arctic Plastic Research Programme of the Fram Centre, we provided new results focusing on several geographical areas: Bjørnøya, Spitsbergen and the Faroe Islands.

In addition to a broad regional approach, our sample sets cover a timeline of 25 years, from 1997 to 2021, and several age classes of the birds, representing different feeding strategies and extent of exposure to plastic. But what have we learned from these studies?

Chicks from the Faroe Islands

Adult fulmars do ingest plastic, but some chicks ingest even more than adults relative to their body weight. In 2020, nineteen out of twenty chicks sampled in Stóra Dímun had plastic in their stomach, with an average of twelve pieces per bird. Not only were they contaminated with plastic, but also with plastic-related chemicals that may be harmful. Both dechloranes and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), used as flame retardants in a range of consumer products such as electronics or building materials, were detected in the livers of all birds.

Although these flame retardants are banned or under restriction in many countries, our findings demonstrate that they are persistent in the environment and travel over long distances to remote ecosystems otherwise low in human populations and direct sources of pollution. The next challenge for the research community is to go beyond the quantification of plastic ingestion and determine the physiological impacts of uptake of associated pollutants. It is hardly conceivable that such contamination has no impact on fitness measures, either for the individual bird, or at the population level.

Fledglings from Svalbard

What happens when the chicks leave the nests? In 2020 and 2021, fulmar fledglings were sampled in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard, to try to answer that question. Plastic was found in 100% of the fledglings sampled, representing in total more than 1800 plastic pieces ingested by young birds, which is a surprising and dramatic result.

Despite the remoteness of Svalbard, the fulmar fledglings there ingest a lot of plastic. Even though they had high loads of plastic in the stomachs, none was found in the intestines. During dissection we observed that a plastic thread had punctured one bird’s intestine wall, raising concerns about the mechanical impacts of plastic ingestion.

The contamination with harmful chemicals (phthalates, PBDE209 and UV stabilisers) was lower in these fledglings than in those from the Faroe Islands. This raises questions about the retention time of those particles in the stomach. Given the difference in the number of plastic fragments between the intestine and the stomach, we expect a long particle residence time in the gizzard – at least a couple months – allowing the pollutants to leach out from the plastic and be distributed in body fluids and tissues.

Adults from Svalbard

Almost 25 years separate our two sample collections of adults in Kongsfjorden (1997-2020). One might expect a lower plastic occurrence from birds sampled in 1997 but our results proved otherwise. In 1997, an average of five plastic pieces were found, similarly to the four pieces ingested by our birds from 2020. This is considerably lower than for both chicks and fledglings, and can in part be explained by parental transfer. To feed their chicks, both parents regurgitate their proventriculus content and offload any ingested plastic along with their stomach oil. In addition, experienced adult fulmars are thought to select their prey more efficiently and to ingest less plastic when feeding.

Now that we know more about the plastic burdens in fulmars from the European Arctic, what are the next challenges and priorities? We believe there is a need for a biomonitoring programme for plastic pollution in the Arctic, such as the one in place in the North Sea. However, in the European Arctic, it is far more challenging to collect beached fulmars as the beaches are remote and carcasses are quickly scavenged by predators such as the arctic fox and the polar bear.

Currently, the most common way to investigate if and how much plastic is ingested is through dissection. But this requires the birds to be sacrificed. Is that really the only solution?

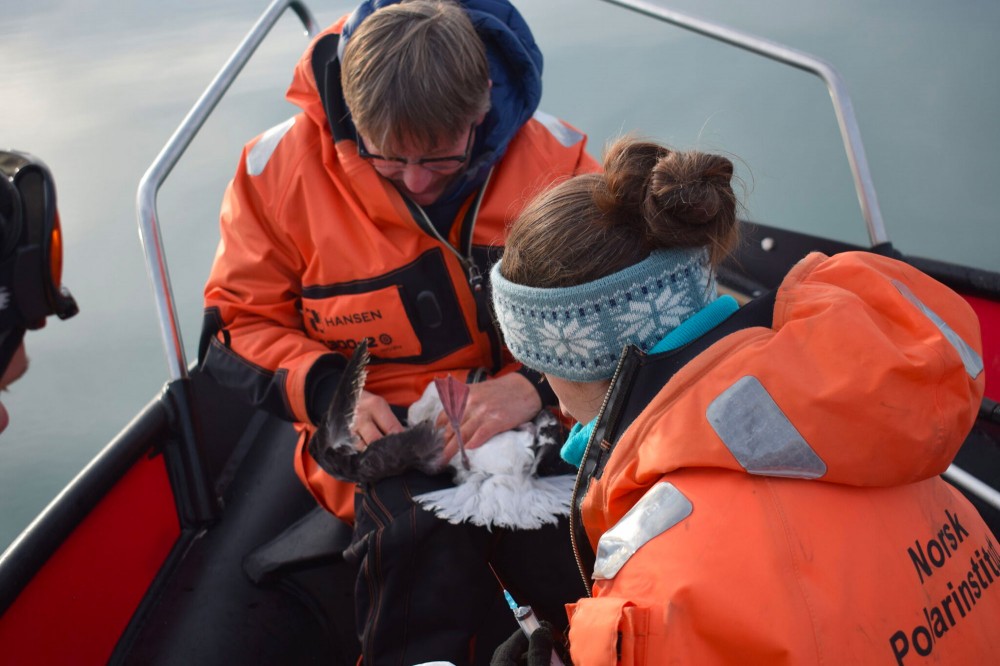

We tackled the ethical dilemma of killing animals for science and developed alternative, non-lethal methods to detect the presence of plastic in birds. Two approaches were tested: the stomach flushing method and ultrasound scanning of birds with subsequent analysis of the images.

Quantification of ingested plastic through stomach flushing

Stomach flushing involves sending water down the bird’s oesophagus to make the animal regurgitate its stomach content. This is a stressful and unpleasant experience for the bird, with unknown impact on stress levels and associated negative effects, such as elevated mortality or reduced fitness. Besides, this method does not allow for the collection of the full stomach content in fulmars due to the constriction between their first and their second stomach.

Our results support this assumption, as very few plastic pieces were retrieved from fulmars whose stomachs were flushed in Bjørnøya in 2018. In the perspective of biomonitoring, this technique should be avoided, and a less invasive, more reliable detection protocol should be developed.

Innovative detection of plastic through imaging technologies

One of the biggest challenges in determining the extent and effect of plastic ingestion in marine wildlife is its detection. Killing is unethical and limits the number of animals that can be used for research. It is even more controversial if the species of interest is endangered. In our PlastFul project we tested three scanning methods for plastic detection to help prevent the waste of animal lives for plastic pollution research: nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), its specialised application magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound scanning.

The ultrasound testing is still in progress but both NMR and MRI imaging were tested, with interesting outcomes. NMR measurements of isolated plastic could discriminate between two different plastic polymers, while MRI scanning on fulmar stomachs stuffed with plastic gave direct and indirect visual evidence that allowed us to trace the contours of two different pieces of plastic.

Therefore, MRI appears to be a promising, non-invasive technology for detecting plastic ingestion in seabirds, but also in any animal large enough to be scanned. The instruments used in this study could be adapted to become portable for practical use in the field. This would open a whole new area of plastic pollution research and monitoring, and could potentially save many lives.

The Northern fulmar

Fulmarus glacialis

- This seabird species can live up to 60 years and becomes sexually mature around 8 years old.

- Fulmars have a gland in their nose that excretes a saline solution to help desalinate their body.

- Fulmars are monogamous and mate for life. They also usually return every year to the same nest site.

- Fulmars produce a stomach oil, which is stored in an “oil tank” above the gizzard. This oily substance is used both as defence against predators and to feed their chick.

- The fulmar is the only vertebrate used so far as a bioindicator of plastic pollution.

This article is originally published in the Fram Forum

The Barents Observer Newsletter

After confirming you're a real person, you can write your email below and we include you to the subscription list.