A deadly polar low – how to forecast it

By: Pernille Amdahl // Norwegian Meteorological Institute

But what is a polar low? Briefly summarised, it is a small, intense low pressure system where the wind increases from weak to strong over a very short timespan.

Everything indicates that this is what sealers experienced in the West Ice area between Jan Mayen and East Greenland in 1952. When the barometer fell and the weather began to change, most of them sensed that they were in for some nasty weather. On 4 April, the hurricane was at its worst. People who were in the area at the time said they felt constant pressure on their eardrums and that they could feel the pressure all over their bodies.

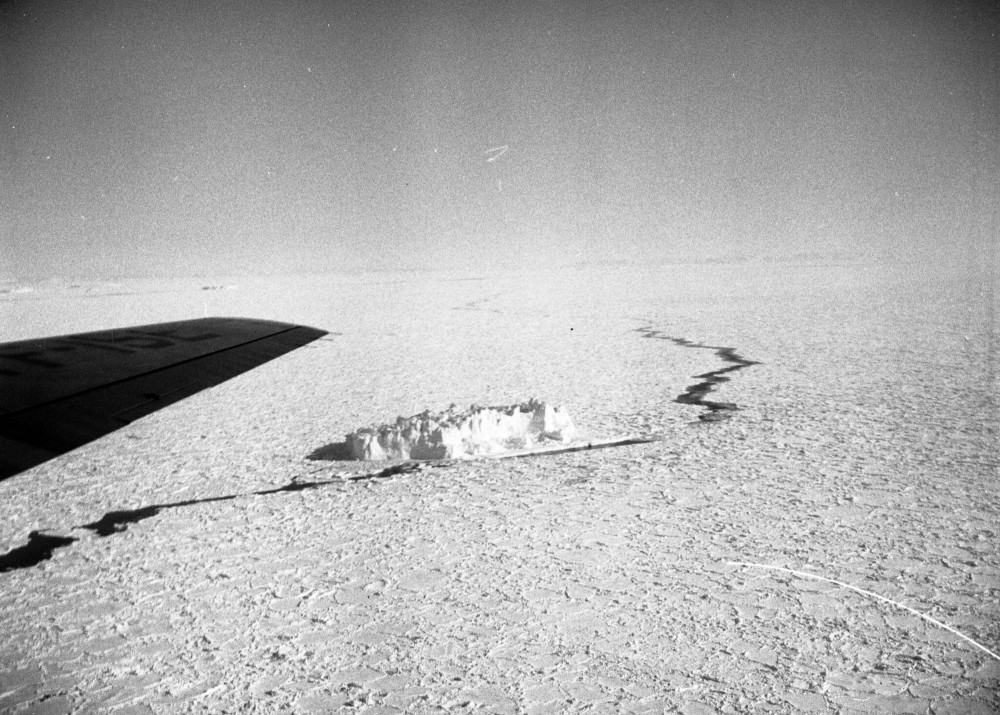

It was difficult to prepare for such a storm before satellites were launched in the 1960s.

Seventy years ago

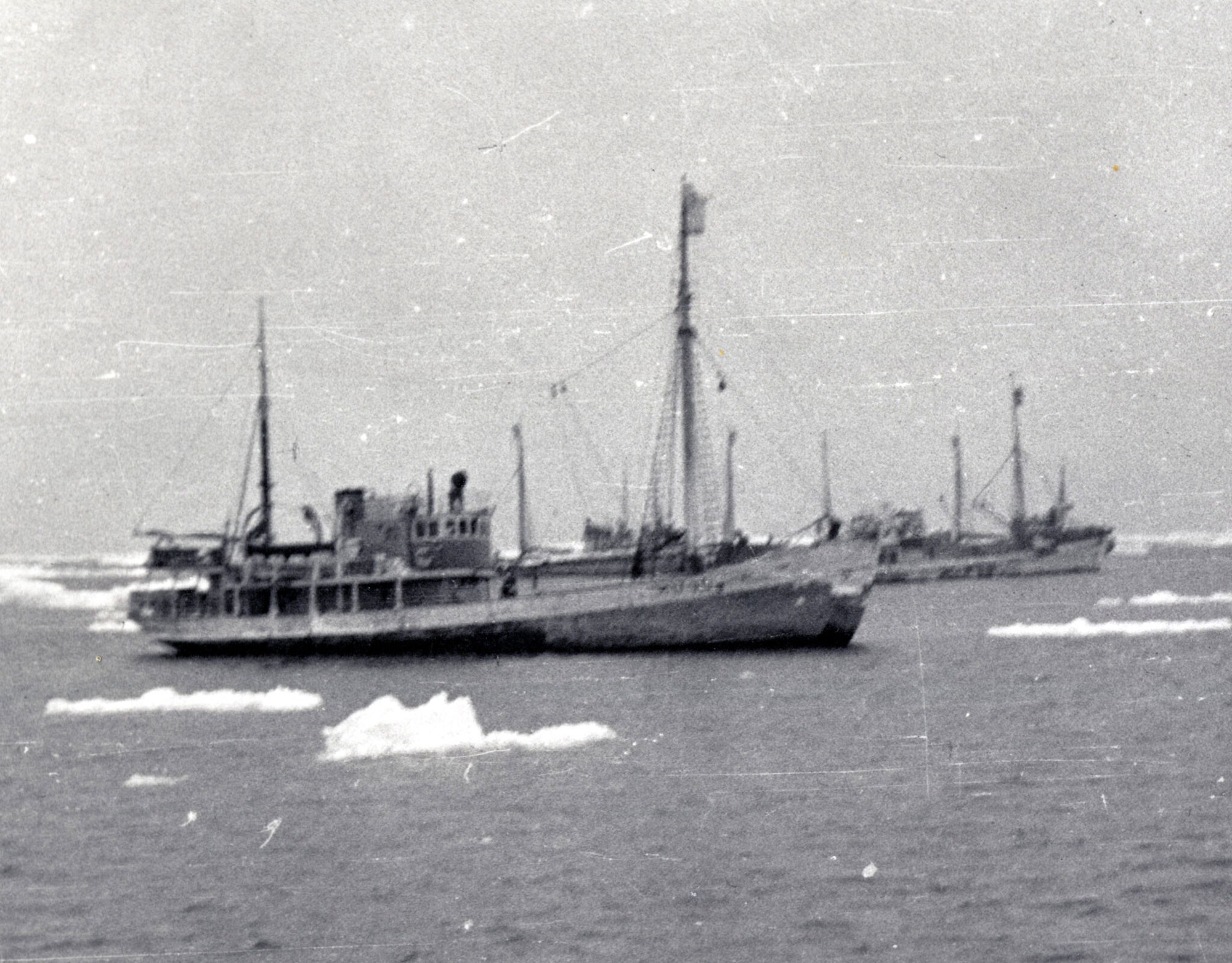

Fifty-three Norwegian ships were located along in West Ice in April 1952. At this time of year, many sealers sailed to this area to hunt. Six of the ships had sailed on to an area located a little further west than the others – an area known for harsh weather and ice conditions.

ADVERTISEMENT

Only one of the six vessels managed to make its way south to Iceland. On the way, one crew member fell overboard and was never found. The other five ships disappeared, along with their crews.

The storm that hit them was extremely fierce. The direction of the wind made it difficult for the ships to seek shelter. There were blizzard conditions and a lot of icing on the ships; hunks of ice were tossed around by the stormy sea.

Despite the lack of eyewitnesses, wreckage or other evidence, there is little doubt that five of the boats were swallowed up by the sea.

The search was called off after about five weeks and the names of the deceased were announced on 7 May. A total of 79 men had died. They were husbands, brothers, friends and sons, natives of Troms and Sunnmøre.

Ninety-eight children had lost their father.

Late forecast

Viewed in retrospect, the weather forecast had underestimated the strength of the wind. In addition, a later storm warning was not issued in time.

Polar lows have been difficult to forecast, and have also throughout history been considered a bit mysterious. Why do they arrive so suddenly, and where do they come from?

The Norwegian Meteorological Institute initiated its first project to strengthen knowledge and forecasts at the beginning of the 1980s. At that time, however, large areas in the north lacked reliable meteorological observations, and long periods of the day were not covered by satellites.

Weather warnings on your mobile

In 2000, work resumed in earnest.

“I would call it a success,” says Gunnar Noer, meteorologist and developer at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

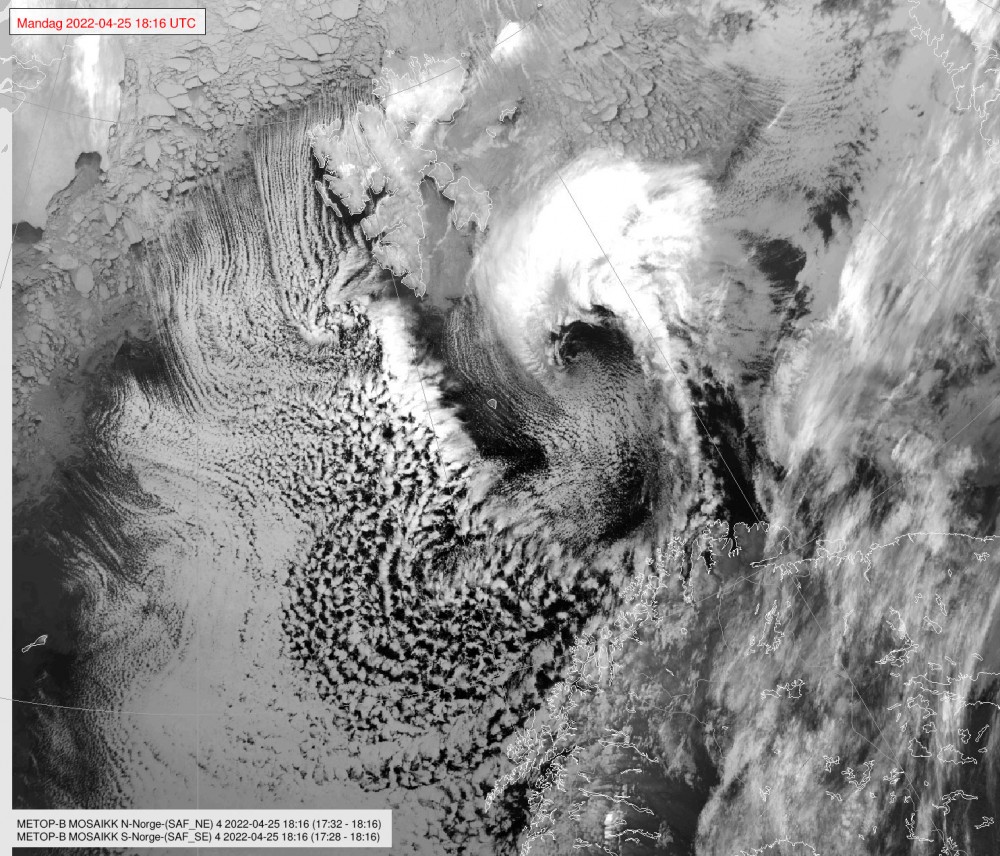

Today, the vast majority of polar lows can be forecast 12-24 hours in advance, some even earlier, but with slightly greater uncertainty. The improvements are mainly due to better coverage from satellite observations. The models have also improved significantly.

“Now we get a better overview of possible outcomes and of the uncertainty in the forecasts. We can also calculate the trajectories of these low pressure systems, which is a great help when we are creating forecasts for the public,” says Noer.

It is still possible to improve the forecasts in terms of geographical location. According to Noer, the forecasts of wind strength and pressure are pretty accurate.

However, the meteorologists’ equipment and models are not the only things that have improved.

“We now have much better communication channels, such as Twitter and BarentsWatch (https://www.barentswatch.no/polarelavtrykk/), that can send weather alerts by text message to those who need them,” says Noer.

Cold meets warm

On average, 13-14 weather events involving one or more polar lows are recorded every year. They are most common in the Barents and Norwegian Seas, occurring when cold air flows from areas with ice and snow over warmer areas of ocean. Polar low season is from October to April, with most forming from January to March.

A polar low lasts anywhere from a few hours to several days.

Low pressure systems form when the air receives heat and moisture from the surface of the ocean. Just like hot smoke, the air rises and cumulonimbus clouds are formed. New air flows in rapidly below these clouds. If other meteorological conditions also produce an unstable mass of air up to an altitude of at least six kilometres, a local low pressure system may form that has its own wind field.

A polar low has developed.

Resembles a cyclone

The average observed maximum wind in a polar low is 21 metres per second. One out of every four polar lows reach or surpass whole gale strength. A polar low resembles the cyclones they have in the tropics, but because the atmosphere is generally colder where we are, our low pressure systems are smaller in both extent and intensity.

The hurricane and polar low along the West Ice in 1952 occurred when a strong area of high pressure full of cold air in the north met a low pressure system full of warm air in the south.

New research

Today, researchers in Norway and abroad are constantly learning new details about how polar lows work. The lows are well suited for testing models that are to be used in climate research. If the models are able to forecast the polar lows, it shows that they also work on cold and Arctic weather types.

The researchers are also interested in analysing historical weather to find out how polar lows arise. Attempts are being made to create automatic recognition systems to identify the low pressure systems based on pure model data or satellite images. If successful, such systems would be able to find trends from previous years, and also make it possible to study trends in the future.

In other words, research on polar lows is important to provide good forecasts for the Arctic climate in the future.

Avalanche warnings

It is also important to test the models used in day-to-day weather forecasting. Ultimately, it is about protecting lives and assets through reliable forecasts that give people time to prepare for the weather.

Nowadays, the coastal population, the fishing fleet, and those involved in shipping are all given good forecasts of polar lows. There have been no direct fatalities related to this type of weather since 2001.

Instead, it is now avalanches related to snowfall from polar lows that poses the greater threat. As winter tourism in northern Norway flourishes, forecasting polar lows grows increasingly important.

This article was originally published by the Fram Forum

The Barents Observer Newsletter

After confirming you're a real person, you can write your email below and we include you to the subscription list.