Why Russian opposition to Putin's war is crucial and how Europe can support

ADVERTISEMENT

Extraordinary circumstances require non-standard approaches to routine issues, such as e.g. writing an op-ed for media. Thus, to make a clear acknowledgment in the very beginning, not in the end: I am among the strongest critics of the Russian ”bad governance” in general, and the Russian war against Ukraine in particular.

However, I am not in the camp of those who call for a complete cut of ties with Russia(ns). We observe this cut in many (if not all) domains, including the one where I have research and applied interest. This is a domain that in a broad sense can be defined as ‘paradiplomacy’, that is, a system of official, semi-official and non-official relations between sub-state (regional and local), non-state (NGOs, business, media, social movements and various private initiatives) and hybrid (e.g. scientific and higher education institutions, or cultural institutions established by the state, region or municipality) actors, located on the different sides of state borders, aimed at finding mutually beneficial solutions to common socio-economic threats and challenges (including issues of conflict-free peaceful coexistence).

This domain includes, among others, numerous institutionalized and non-institutionalized structures, processes, and initiatives. Among others, I can name the programs of the European Neighborhood Instrument from the Barents to the Baltic Sea, the structures and institutions of cross-border cooperation, primarily the BEAR, Euroregion “Karelia”, Euroregion “Baltic”, etc., sister city movement, academic cooperation, joint research and double degree educational programs, and so on. As researcher and human individual living in northern Europe, I share the vision underlying the need to maintain at least the minimally acceptable level of interaction with Russia and Russians.

There are many sane Russians, and they continue to resist.

At the very beginning of the war, when it was still possible to somehow trust public opinion polls, every fourth respondent in Russia spoke out against the war. I have reasonable suspicions that there are much more people with clear anti-military positions. Why am I coming to such a conclusion?

In a situation when no quantitative analysis is possible in principle, it remains to be judged by some important indirect signs. One of them is what people write and how they behave in Russian social networks. In recent weeks, I began to visit more often ‘Vkontakte’, the ‘Russian Facebook’. At first, it seemed to me that it is a pure hell: almost no one writes anti-war posts, and under the posts about the war there are only hysterical-patriotic-Orthodox comments.

So, last week the Karelian governor Artur Parfenchikov posted the news about the awarding of a Russian soldier (born in my next-to-native Karelian, earlier Finnish, village of Naistenjärvi) with the medal “For Courage”. I expected that in addition to enthusiastic comments there would also be adequate ones – that it is wrong, illegal, and criminal to fight in a foreign country and kill people. I haven’t found those. And, to put it mildly, I was very upset. And I was even more upset with the fact that more than 90% of the comments were left by women. I am still in shock with this.

ADVERTISEMENT

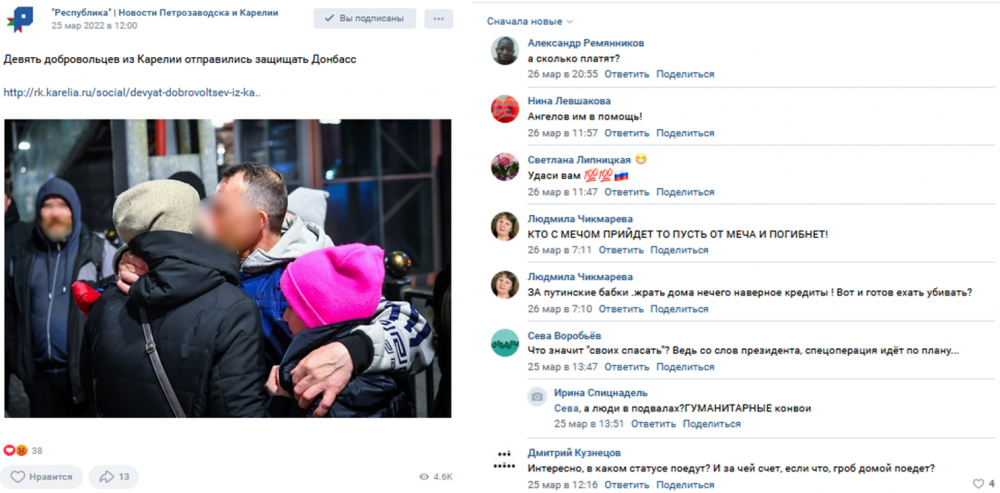

But just a couple of days ago, governor Parfenchikov posted about the departure of nine Karelian volunteers fighters to the war “in Donbas”. This is in itself terrible news. But here’s what I’ve noticed, and what gives me hope: under this post there were very many adequate comments. A short time after the post appeared, I read those comments and could not believe my eyes: almost every third comment was anti-war. A day later, I returned to the page of the governor in search for continuation. And what I saw was that anti-war comments have been deleted, although not immediately (apparently, there are not enough moderators’ workforce). And those comments which remained, get not only a lot of hate, but also a lot of ‘like’ signs, a lot of likes indeed.

The press secretary of the Karelian governor, Marina Kabatyuk, who reposted the photos of the ‘heroes’-volunteers on her page, completely closed the comments section, explaining this with an ‘invasion of bots.’ In fact, she was afraid that people would express their position more openly on her account than on the official page of the governor. She could just drown in the ‘wrong’ comments. In measurable numbers, there are about 900 ‘likes’ under the post about volunteer fighters, that is, about 4% of those who viewed the post (ca. 22k). On the governor’s page, the situation is even more revealing: 4,200 likes per 160,000 views, that is, approximately 2.5%. And under the same news on the page of the popular government-owned media ‘Respublika’ there are almost no likes, and mainly anti-war comments.

I do not dare to claim that this is the real figure of support for the war. Judging by the stories of relatives and friends living in Russia, the support is far higher. But the very fact that people do not openly (by clicking ‘like’) support the war is already a good sign. Not to mention the fact that under aggressive military censorship people have the bravery to openly, under their own name, voice against the war on the official page of the insane governor, driving around the city with ‘Zwastika’ on his Toyota Landcruiser.

Sane and brave Russians must be supported, this is VERY important!

Now all the attention of Europe is turned to Ukraine. And it cannot beotherwise as children, women, elderly people are being killed there, as well as thousands of soldiers. This madness must be stopped as soon as possible.

And yet, after the “hot” phase of the war ends, the time comes to think about the post-war future (I reject the option of a nuclear confrontation, not because it is impossible, but because in this case it makes no sense to talk about the future). Russia will not disappear from the physical map of the world; it will still be a neighbor of Europe and an important part of the Arctic. There will remain 140+ millions of Russians living next door.

The West has contributed to the education and upbringing of many progressively-minded people who remain in Russia and remain friends of Europe, friends of the world (and peace; interestingly, there is the same word for ‘world’ and ‘peace’ in Russian, ‘mir’). The West(ern establishment) is to some degree responsible for the fact that Putin is at war with Ukraine (this responsibility is a matter for a separate big discussion), but also “for those whom they have tamed” (“The Little Prince”) in Russia. Refusing to interact with these people means betraying them, acting mercilessly, contrary to Western values. This applies to many people, both ordinary people and employees of the NGOs, media, business, academia and so on. As a Russian national living and working in Europe, I can’t help thinking about those who remain in Russia, who continue to resist, who promote—openly or behind the scenes—the peace agenda.

Europeans should clearly understand that to have an anti-war say in modern Russia is close to a heroic deed. Those who voice their anti-military position are being arrested, imprisoned, sacked from work, sent down from studies, suffer from pressure in everyday life.

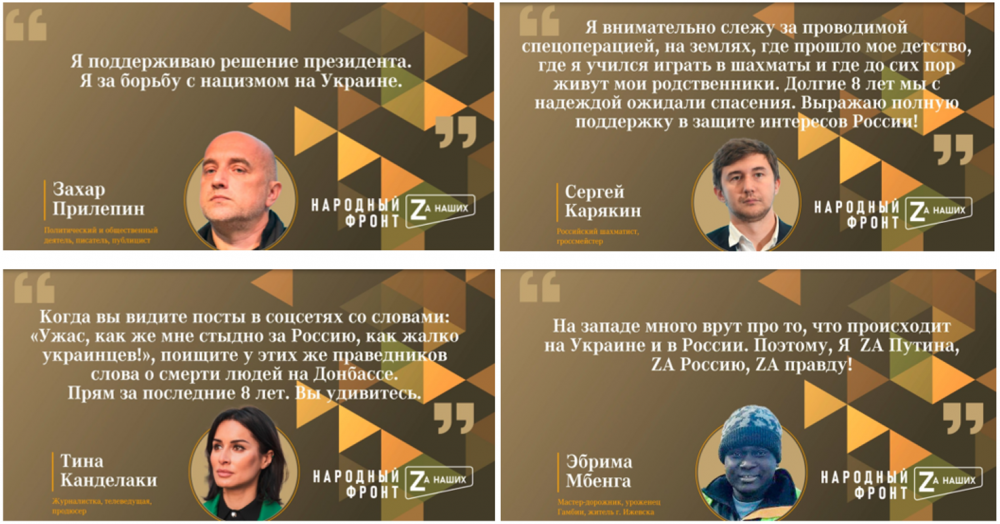

I can say more: even mentally resisting propaganda is close to a miracle. The propaganda had been very strong for decades, it started from the daycare and continue throughout the whole life. There is a generation of those who have never seen another president but Putin and another Russia but Putin’s Russia. Currently, the war propaganda continues everywhere: in mass media, in educational institutions, at work etc. Official videos with propaganda are becoming a compulsory part of office life (remember Orwell’s ‘Two Minutes Hate’ described in ‘1984’). In those videos, not only officials but also public opinion leaders and ordinary Russians reproduce fake news and values. Even the well-known investigative journalist Christo Grozev (‘Billingcat’) had to admit that after half-an-hour watching of Russian ‘First channel’ he had to go and check that the ‘facts’ they presented to the viewers are fake, not real. How do you imagine ordinary Russian resisting that? Almost no chance.

By the way, as one of the ‘unconventional’ commentators rightly noted: why are the hero-volunteers appearing in all the photographs with blindfolded eyes? “Why be afraid? What are they shy about?” – asked the commentator.

How to continue relations with sane Russia(ns)? There might be different ways to go on, however, none of them seems indisputable. What lay on the surface is the fact that people-to-people relations have always been primarily based on trust among the parties. This may be a good background for further steps: I personally know many people in Russia whom I trust and am ready to vouch for. I believe that those who (used to) have friends and who work(ed) with Russian colleagues can name those in Russia who deserve to remain in the cooperation networks. There might be a kind of “green list” of those with whom we’d like to continue our cooperation. This goes for Russian people involved in different networks: business, culture, education and research, sister cities movement and even local and regional administrations.

They will also be the core of post-war and post-Putin Russia’s new leadership.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Barents Observer Newsletter

After confirming you're a real person, you can write your email below and we include you to the subscription list.