Warmer sea and less ice north of Svalbard

Text by Helge Markusson, Fram Centre

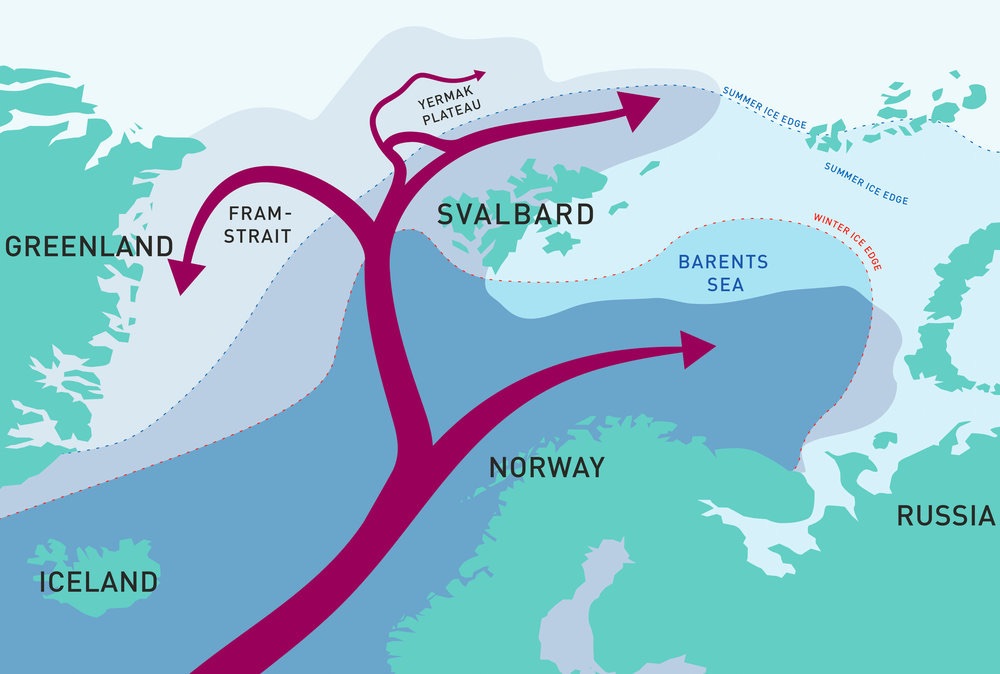

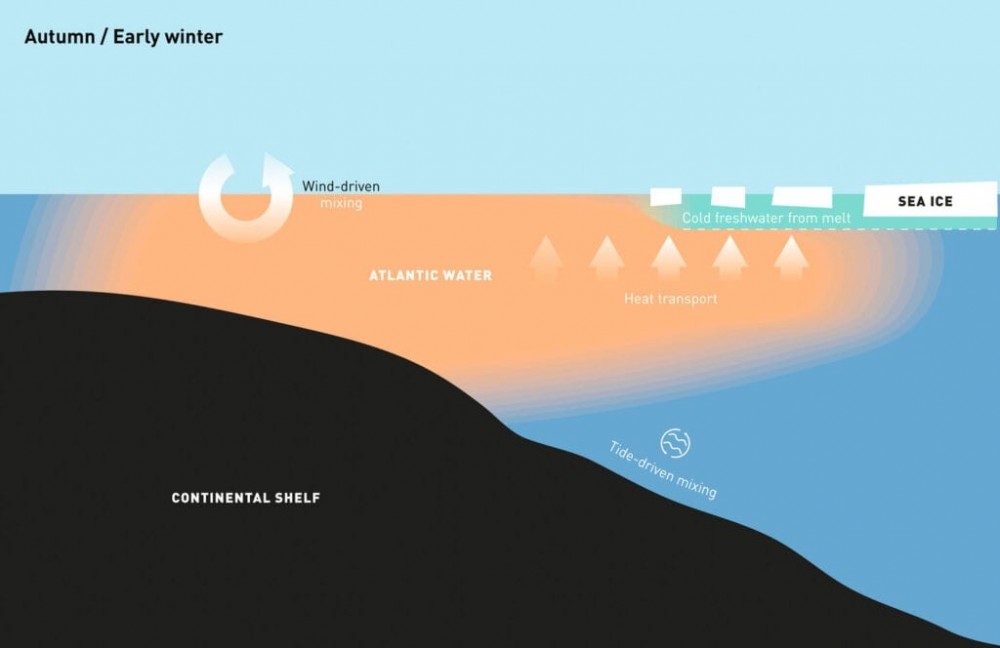

A new study shows that the largest influx toward the Arctic Ocean takes place in autumn and early winter and that the water is also warmest at this time of year.

Powerful pulses of water warmer than five degrees enter the area at the time of the year when the sea ice should freeze. But even if the air temperature is far below freezing, even during the months without the sun to warm the ground, new sea ice fails to appear.

«Only if the wind helps by blowing ice and fresh surface water from the interior of the Arctic Ocean or from the east will we see an ice cover on the Atlantic influx. We have been watching the ice cover on the Arctic Ocean become significantly thinner in recent years, along with reductions in distribution in time and space. This also reduces the supply of fresh water from the north,» quotes Angelika Renner, an oceanographer at the Marine Research Institute and one of the researchers behind the study.

The mechanism that causes the warm and salty waters from the south to remain below the insulating cold and fresh layer of water in the north appears to have been weakened in recent years.

ADVERTISEMENT

More open waters in the north and east

A research paper was published this summer that shows how the northern Barents Sea is about to shift from an Arctic to an Atlantic climate.

«We see a similar atlantification of the sea to the north and east of Svalbard; less sea ice in the Arctic Ocean leads to less melt-water and thus the warm Atlantic water remains atop the water column for most of the year, staying entirely on the surface. It provides a larger ice-free area north of the Svalbard Archipelago and thinner ice further to the east,» quotes Arild Sundfjord, an oceanographer at the Norwegian Polar Institute

Sundfjord and Renner point out that the Atlantic influx brings nutrients with it which are necessary for the growth of phytoplankton and larger organisms such as copepods.

«This allows the fish which feed on such zooplankton to survive farther north. So it is not just the physical environment that is changing; the ecosystem is changing as well. Research shows that global warming has sent a number of fish species in the Barents Sea farther northeast, at relatively great speed. We really need to keep our eyes open and monitor what is happening north of Svalbard,» quotes Sundfjord.

Warmer storms

In an article in the Norwegian newspaper, Aftenposten, Renner and Sundfjord wrote that the wind also plays an important role in how the ice sheet forms. Southwest winds can reinforce the influx of Atlantic water from the south. The wind blows ice and the cold, fresh surface water towards the northeast, which allows for saltier and warmer waters on the surface. At the same time, strong winds help the heat mix more effectively up to the surface and thus can prevent the freezing of ice even at very low air temperatures.

«Northern winds cause the cold freshwater and ice to be carried south. In some years, this might lead to ice-covered waters quite far south. We saw this in 2014 when the wind brought ice so far south that several of the expeditions to the Marine Research Institute and the Norwegian Polar Institute entered areas that had been ice-free in autumn in past years,» quotes Sundfjord.

«And we did not need to send temperature gauges very far into the water column before they registered warmer water. There could be ice on the surface and a temperature of seven degrees at a depth of 30 feet in the water column at the same place. The ice cover in 2014 was thus a result of the weather, not the climate. The wind thus threw the local ice cover over the more extensive climate problems,» quotes Renner.

This story is originally published on the website of the Fram Centre