2023 was warmest year on record “by a huge margin,” says WMO

ADVERTISEMENT

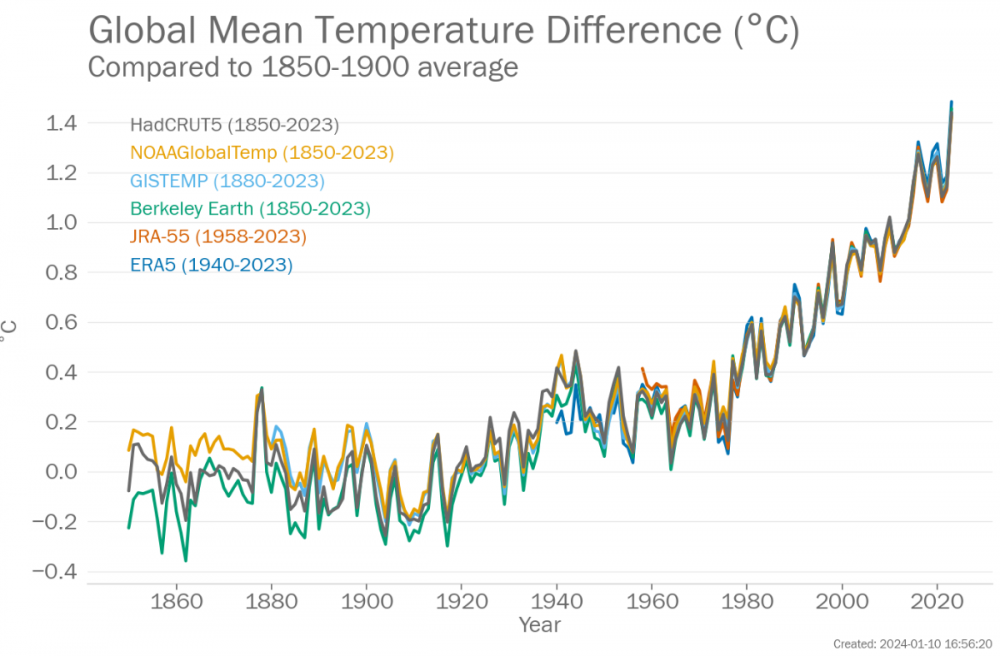

The annual average global temperature for the year exceeded pre-industrial levels (1850-1900) by 1.45 C, the organization said.

“Humanity’s actions are scorching the earth,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres said in statement.

“2023 was a mere preview of the catastrophic future that awaits if we don’t act now. We must respond to record-breaking temperature rises with path-breaking action.”

July and August recorded exceptionally hot months, while new monthly records were also set between June and December.

Paris agreement

The WMO described the 2023 annual global temperature as “symbolic” given the Paris climate agreement target seeks to control the rise in temperature averaged over decades to not exceed 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels.

“We can still avoid the worst of climate catastrophe. But only if we act now with the ambition required to limit the rise in global temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius and deliver climate justice,” Guterres said.

ADVERTISEMENT

WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo said the shift from La Niña to El Niño in the middle of year contributed to the higher temperatures (La Niña is a climate pattern that cools sea surface temperature, while El Niño warms the sea surface temperature), but that anthropogenic impacts are affecting temperature rise long term.

“While El Niño events are naturally occurring and come and go from one year to the next, longer term climate change is escalating and this is unequivocally because of human activities,” Saulo said.

The WMO used six datasets to make their calculations.

The are from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (NASA GISS); the United Kingdom’s Met Office Hadley Centre and the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit (HadCRUT); and the Berkeley Earth Group.

Reanalysis datasets from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts and its Copernicus Climate Change Service, along with the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), are also used.

The information is gathered through observing sites, ships, global marine network buoys, marine observations and satellites.

Saulo said she hopes the most recent analysis spurs decision makers to recommit to reaching the Paris agreement climate targets.

“We cannot afford to wait any longer. We are already taking action but we have to do more and we have to do it quickly,” she said.

“We have to make drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and accelerate the transition to renewable energy sources.”

This story is posted on the Barents Observer as part of Eye on the Arctic, a collaborative partnership between public and private circumpolar media organizations.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Barents Observer Newsletter

After confirming you're a real person, you can write your email below and we include you to the subscription list.